It’s my birthday. I’m into my seventh decade. Born in ’61, now 61.

My first decade was one of being shy and smart and tall and skinny and bullied. My second decade was one of growth: growing out of everything, from my clothes to my hometown. Cruising into my twenties I became independent and anxious and happy. By my thirties, I became responsible. In my forties, I became lost. In my fifties, I was crushed.

I expected worst things still to fall on me in my sixth decade, and I was surprised instead by things that uplifted me. Where I will land in my seventh decade, I don’t know. On good days I look to remain open, on bad days I hope for a close.

In all that time, with rare exception, I have taken off every day since I started working in the early 80s. Often those free days were filled with simple pleasures. Mixed in with that was some contemplation.

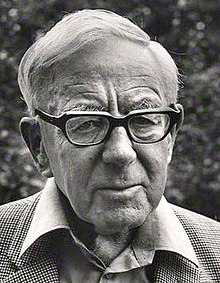

I think two good things to contemplate on this day are these two essays by Oliver Sacks. One was written when he was still vibrant and turning 80: Opinion | The Joy of Old Age. (No Kidding.) in The New York Times. The second one when he was dying of cancer not much more than a year later: Opinion | Oliver Sacks on Learning He Has Terminal Cancer, also The New York Times.

What impression they will leave on will depend on your current perspective. I encourage you to move around, literally and figuratively, to have to best perspective on life that you can have. The days will be what they are, regardless. How you perceive them depends on where you stand and how you look out.

So there’s a new

So there’s a new