Last week Paul Kedrosky & Eric Norlin of SKV wrote this piece, Society’s Technical Debt and Software’s Gutenberg Moment, and several smart people I follow seemed to like this and think it something worthwhile. It’s not.

It’s not worthwhile because Kedrosky and Norlin seem to know little if anything about software. Specifically, they don’t seem to know anything about:

- software development

- the nature of programming or coding

- technical debt

- the total cost of software

Let me wade through their grand and woolly pronouncements and focus on that.

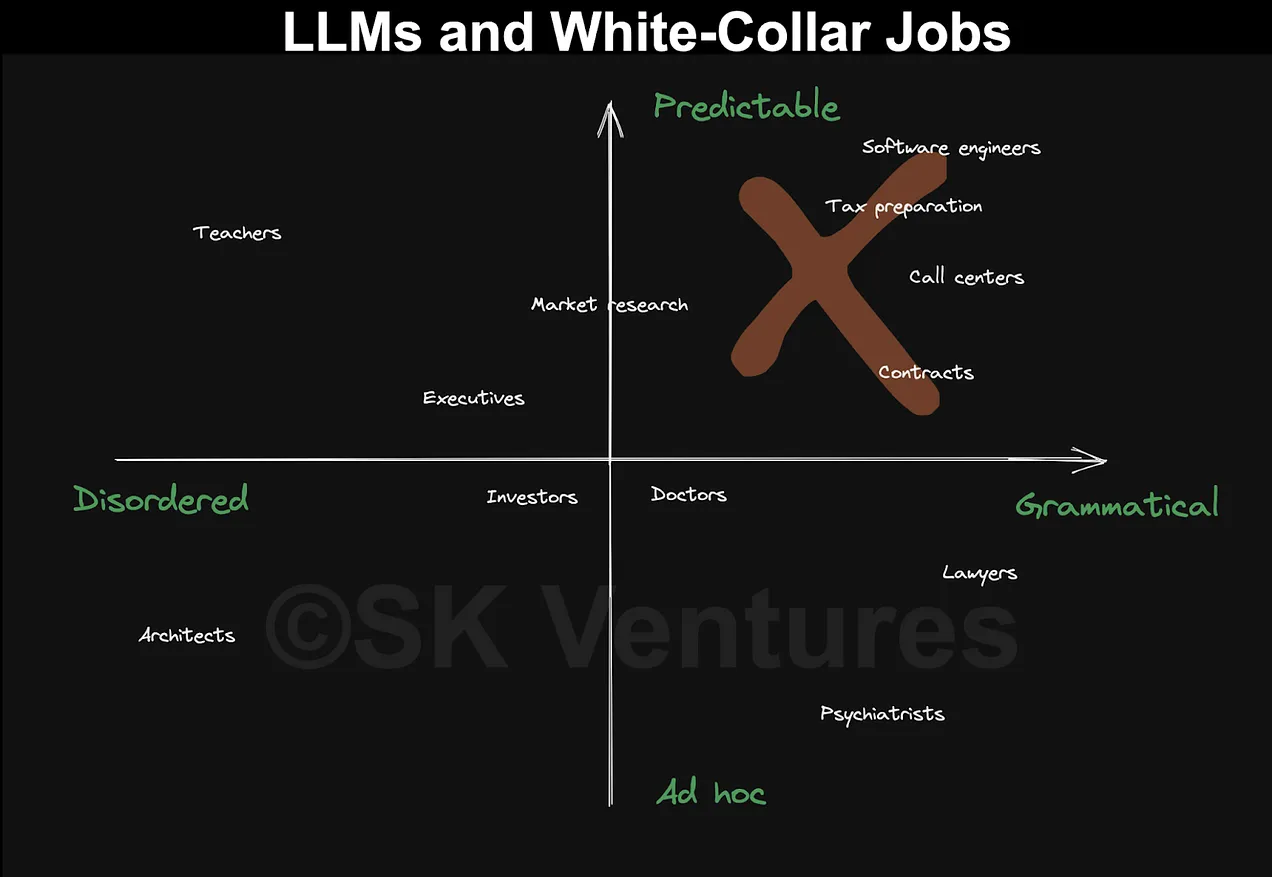

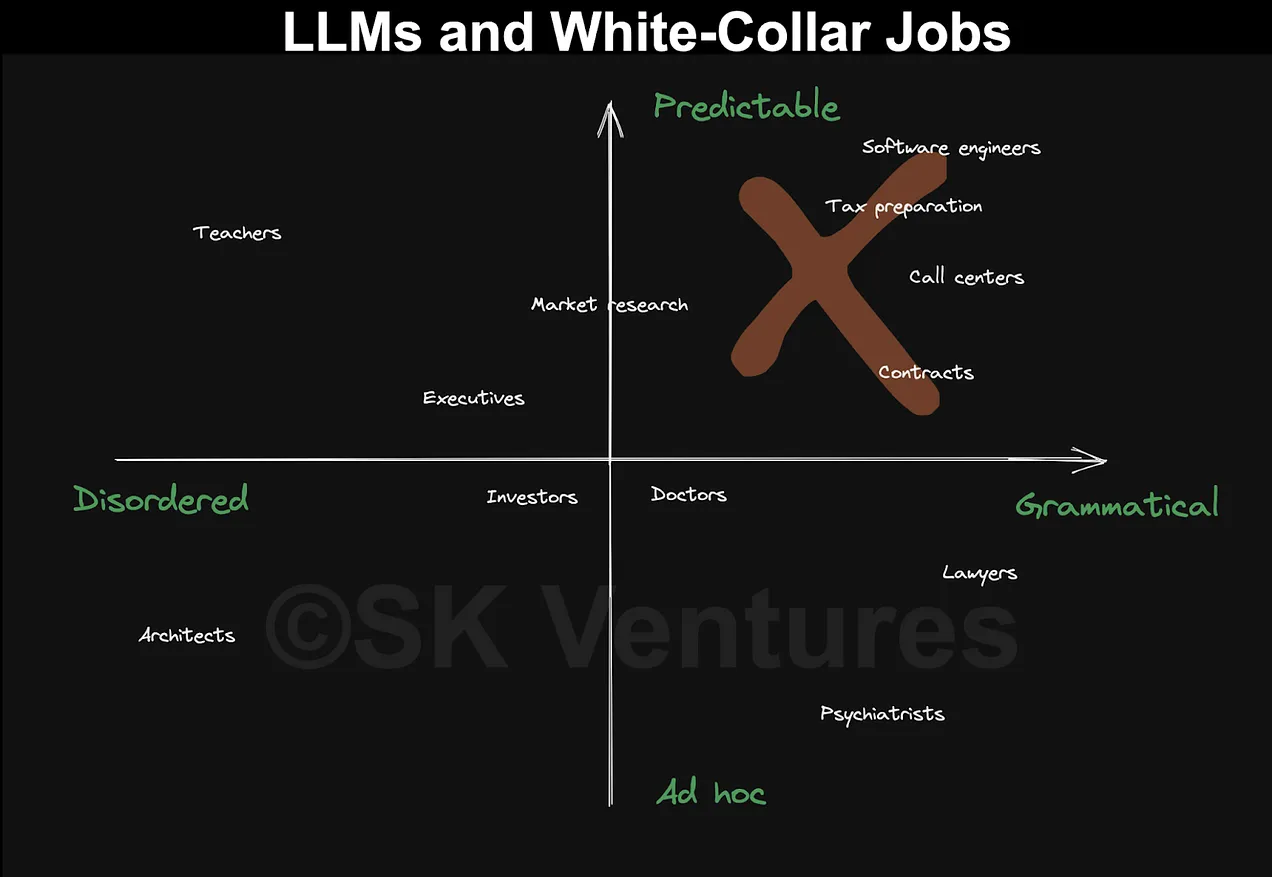

They don’t understand software development: For Kedrosky and Norlin, what software engineers do is predictable and grammatical. (See chart, top right).

To understand why that is wrong, we need to step back. The first part of software development and software engineering should start with requirements. It is a very hard and very human thing to gather those requirements, analyze them, and then design a system around them that meets the needs of the person(s) with the requirements. See where architects are in that chart? In the Disordered and Ad hoc part in the bottom left. Good IT architects and business analysts and software engineers also reside there, at least in the first phase of software development. To get to the predictable and grammatical section which comes in later phases should take a lot of work. It can be difficult and time consuming. That is why software development can be expensive. (Unless you do it poorly: then you get a bunch of crappy code that is hard to maintain or has to be dramatically refactored and rewritten because of the actual technical debt you incurred by rushing it out the door.)

Kedrosky and Norlin seem to exclude that from the role of software engineering. For them, software engineering seems to be primarily writing software. Coding in other words. Let’s ignore the costs of designing the code, testing the code, deploying the code, operating the code, and fixing the code. Let’s assume the bulk of the cost is in writing the code and the goal is to reduce that cost to zero.

That not just my assumption: it seems to be their assumption, too. They state: “Startups spend millions to hire engineers; large companies continue spending millions keeping them around. And, while markets have clearing prices, where supply and demand meet up, we still know that when wages stay higher than comparable positions in other sectors, less of the goods gets produced than is societally desirable. In this case, that underproduced good is…software”.

Perhaps that is how they do things in San Francisco, but the rest of the world has moved on from that model ages ago. There are reasons that countries like India have become powerhouses in terms of software development: they are good software developers and they are relatively low cost. So when they say: “software is chugging along, producing the same thing in ways that mostly wouldn’t seem vastly different to developers doing the same things decades ago….(with) hands pounding out code on keyboards”, they are wrong because the nature of developing software has changed. And one of the way it has changed is that the vast majority of software is written in places that have the lowest cost software developers. So when they say “that software cannot reach its fullest potential without escaping the shackles of the software industry, with its high costs, and, yes, relatively low productivity”, they seem to be locked in a model where software is written they way it is in Silicon Valley by Stanford educated software engineers. The model does not match the real world of software development. Already the bulk of the cost in writing code in most of the world has been reduced not to zero, but to a very small number compared to the cost of writing code in Silicon Valley or North America. Those costs have been wrung out.

They don’t understand coding: Kedrosky and Norlin state: “A software industry where anyone can write software, can do it for pennies, and can do it as easily as speaking or writing text, is a transformative moment”. In their piece they use an example of AI writing some Python code that can “open a text file and get rid of all the emojis, except for one I like, and then save it again”. Even they know this is “a trivial, boring and stupid example” and say “it’s not complex code”.

Here’s the problem with writing code at least with the current AI. There are at least three difficulties that AI code generators suffers from: triviality, incorrectness, and prompt skill.

First, the problem of triviality. It’s true: AI is good at making trivial code. It’s hard to know how machine learning software produces this trivial code, but it’s likely because there are lots of examples of such code on the Internet for them to train on. If you need trivial code, AI can quickly produce it.

That said, you don’t need AI to produce trivial code. The Internet is full of it. (How do you think the AI learned to code?) If someone who is not a software developer wants to learn how to write trivial code they can just as easily go to a site like w3schools.com and get it. Anyone can also copy and paste that code and it too will run. And with a tutorial site like w3schools.com the explanation for the code you see will be correct, unlike some of the answers I’ve received from AI.

But what about non-trivial code? That’s where we run into the problem of incorrectness. If someone prompts AI for code (trivial or non-trivial) they have no way of knowing it is correct, short of running it. AI can produce code quickly and easily for you, but if it is incorrect then you have to debug it. And debugging is a non-trivial skill. The more complex or more general you make your request, the more buggy the code will likely be, and the more effort and skill you have to contribute to make it work.

You might say: incorrectness can be dealt with by better prompting skills. That’s a big assumption, but let’s say it’s true. Now you get to the third problem. To get correct and non-trivial outputs — if you can get it at all, you have to craft really good prompts. That’s not a skill anyone will have. You will have to develop specific skills — prompt engineering skills — to be able to have the AI write python or Go or whatever computer language you need. At that point the prompt to produce that code is a form of code itself.

You might push back and say: sure, the prompts might be complex, but it is less complicated than the actual software I produce. And that leads to the next problem: technical debt.

They don’t understand technical debt: when it comes to technical debt, Kedrosky and Norlin have two problems. First, they don’t understand the idea of technical debt! In the beginning of their piece they state: “Software production has been too complex and expensive for too long, which has caused us to underproduce software for decades, resulting in immense, society-wide technical debt.”

That’s not how those of us in the IT community define it. Technical debt is not a lack of software supply. Even Wikipedia knows better: “In software development, technical debt (also known as design debtor code debt) is the implied cost of future reworking required when choosing an easy but limited solution instead of a better approach that could take more time”. THAT is technical debt.

One of the things I do in my work is assess technical debt, either in legacy systems or new systems. My belief is that once AI can produce code that is non-trivial and correct and based on prompts, we are going to get an explosion of technical debt. We are going to get code that appears to solve a problem and do so with a volume of python (or Java or Go or what have you) that the prompt engineer generated and does not understand. It will be like copy and paste code amplified. Years from now people will look at all this AI generated code and wonder why it is the way it is and why it works the way it does. It will take a bunch of counter AI to translate this code into something understandable, if that will even be possible. Meanwhile companies will be burdened with higher levels of technical debt accelerated by the use of AI developed software. AI is going to make things much worse, if anything.

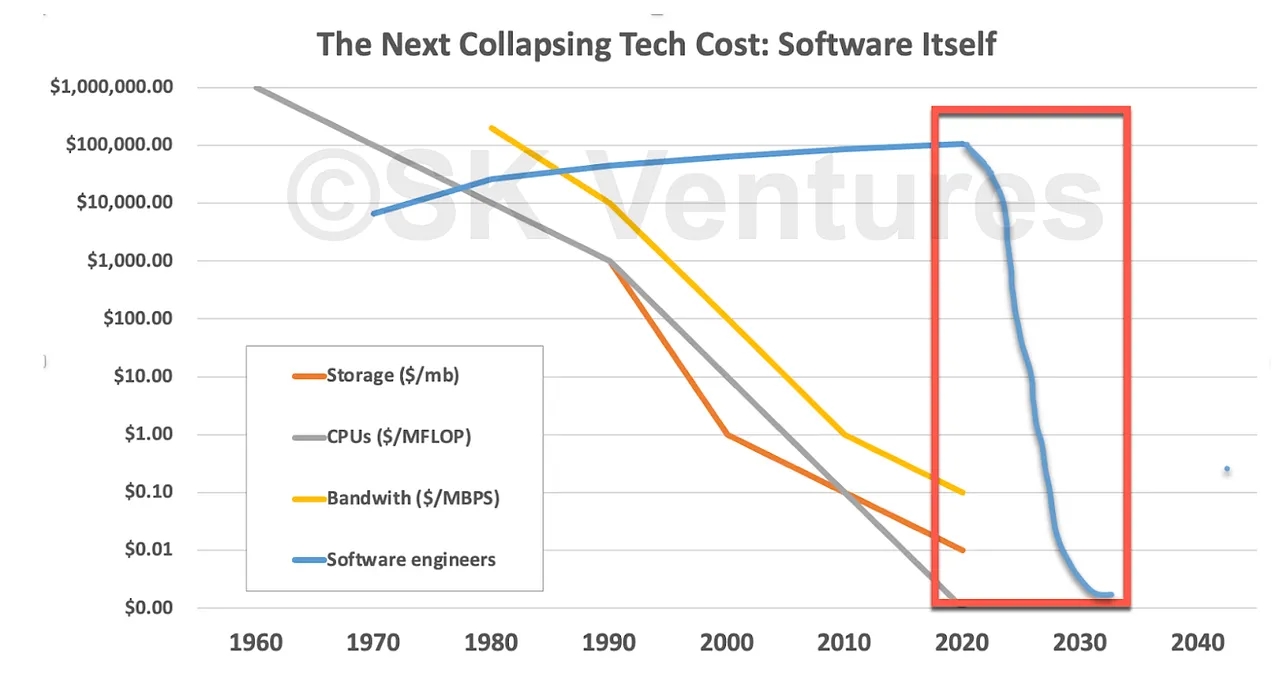

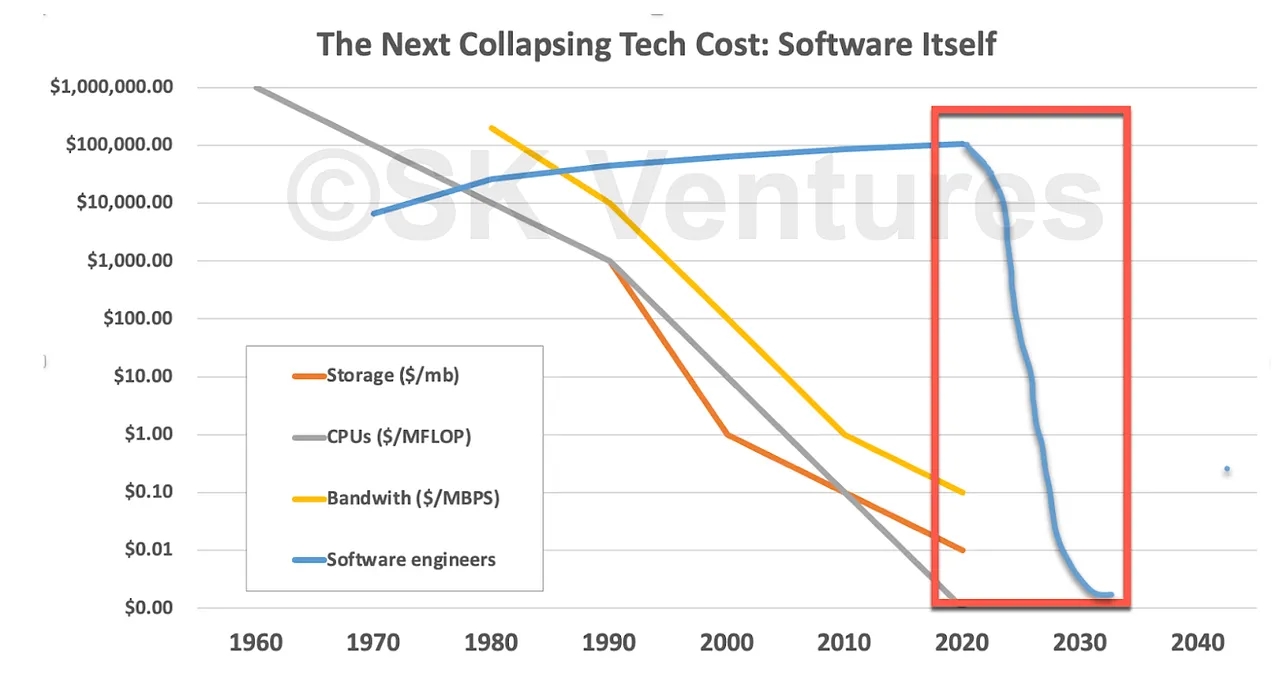

They don’t understand the total cost of software: Kedrosky and Norlin included this fantasy chart in their piece.

First off, most people or companies purchase software, not software engineers. That’s the better comparison to hardware. And if you do replace “Software engineers” with software, then in certain areas of software this chart has already happened. The cost of software has been driven to zero.

What drove this? Not AI. Two big things that drove this are open source and app stores.

In many cases, open source eliminated the (licensing) cost of software to zero. For example, when the web first took off in the 90s, I recall Netscape sold their web server software for $10,000. Now? You can download and run free web server software like nginx on a Raspberry Pi for free. Heck can write your own web server using node.js.

Likewise with app stores. If you wanted to buy software for your PC in the 80s or 90s, you had to pay significantly more than 99 cents for it. It certainly was not free. But the app stores drove the expectation people had that software should be free or practically free. And that expectation drove down the cost of software.

Yet despite developments like open source and app stores driving the cost of software close to zero, people are organizations are still paying plenty for the “free” software. And you will too with AI software, whether it’s commercial software or software for your personal use.

I believe that if you have AI generating tons of free personal software, then you will get a glut of crappy apps and other software tools. If you think it’s hard to determine good personal software now, wait until that happens. There will still be good software, but to develop that will cost money, and that money will be recovered somehow, just like it is today with free apps with in app purchases or apps that steal your personal information and sell it to others. And people will still pay for software from companies like Adobe. They are paying for quality.

Likewise with commercial software. There is tons of open source software out there. Most of it is wisely avoided in commercial settings. However the good stuff is used and it is indeed free to licence and use.

However the total cost of software is more than the licencing cost. Bad AI software will need more capacity to run and more people to support, just like bad open source does. And good AI software will need people and services to keep it going, just like good open source does. Some form of operations, even if it is AIOps (another cost), will need expensive humans to insure the increasing levels of quality required.

So AI can churn out an tons of free software. But the total cost of such software will go elsewhere.

To summarize, producing good software is hard. It’s hard to figure out what is required, and it is hard to design and built and run it to do what is required. Likewise, understanding software is hard. It’s called code for a reason. Bad code is tough to figure out, but even good code that is out of date or used incorrectly can have problems and solving those problems is hard. And last, free software has other costs associated with it.

P.S. It’s very hard to keep up and counter all the hot takes on what AI is going to do for the world. Most of them I just let slide or let others better than me deal with. But I wanted to address this piece in particular, since it seemed influential and un-countered.

P.S.S. Beside all that above, they also made some statements that just had me wondering what they were thinking. For example, when they wrote: “This technical debt is about to contract in a dramatic, economy-wide fashion as the cost and complexity of software production collapses, releasing a wave of innovation.” Pure hype.

Or this : “Software is misunderstood. It can feel like a discrete thing, something with which we interact. But, really, it is the intrusion into our world of something very alien. It is the strange interaction of electricity, semiconductors, and instructions, all of which somehow magically control objects that range from screens to robots to phones, to medical devices, laptops, and a bewildering multitude of other things.” I mean, what is that all about?

And this: “The current generation of AI models are a missile aimed, however unintentionally, directly at software production itself”. Pure bombast.

Or this hype: “They are “toys” in that they are able to produce snippets of code for real people, especially non-coders, that one incredibly small group would have thought trivial, and another immense group would have thought impossible. That. Changes. Everything.”

And this is flat up wrong: “This is just the beginning (and it will only get better). It’s possible to write almost every sort of code with such technologies, from microservices joining together various web services (a task for which you might previously have paid a developer $10,000 on Upwork) to an entire mobile app (a task that might cost you $20,000 to $50,000 or more).”

There was a lot of chatter around private jets last week as a result of

There was a lot of chatter around private jets last week as a result of

Is this interview of

Is this interview of

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7835595/alfanifig1.png)