Is Elon Musk incompetent? Is he a genius? Or is he something else?

While some think his recent actions at Twitter and in DOGE indicate he is incompetent, Noah Smith came out and defended Musk in this Substack post: Only fools think Elon is incompetent – by Noah Smith.

Smith starts off by saying that Musk …

is a man of well above average intellect.

Let’s just pass on that, since we don’t know the IQ or any other such measure of the intellect of Musk. Plus, competent people don’t need to have a high IQ.

Indeed Smith gives up on IQ and goes for another measure:

And yet whatever his IQ is, Elon has unquestionably accomplished incredible feats of organization-building in his career. This is from a post I wrote about Musk back in October, in which I described entrepreneurialism as a kind of superpower

So it’s not high IQ that makes Elon Musk more competent than most, it’s his entrepreneurialism. In case you think anyone could have the same ability, Smith goes on the say why Musk is more capable than most of us:

Why would we fail? Even with zero institutional constraints in our way, we would fail to identify the best managers and the best engineers. Even when we did find them, we’d often fail to convince them to come work for us — and even if they did, we might not be able to inspire them to work incredibly hard, week in and week out. We’d also often fail to elevate and promote the best workers and give them more authority and responsibilities, or ruthlessly fire the low performers. We’d fail to raise tens of billions of dollars at favorable rates to fund our companies. We’d fail to negotiate government contracts and create buzz for consumer products. And so on.

Smith then drives home this point by saying:

California is famously one of the hardest states to build in, and yet SpaceX makes most of its rockets — so much better than anything the Chinese can build — in California, almost singlehandedly reviving the Los Angeles region’s aerospace industry. And when Elon wanted to set up a data center for his new AI company xAI — a process that usually takes several years — he reportedly did it in 19 days

And because of all that, Smith concludes:

Elon Musk is, in many important ways, the single most capable man in America, and we deny that fact at our peril.

Reading all that, you might be willing to concede that whatever Musk’s IQ is, not only is he more than competent, but he must be some sort of genius to make his companies do what they do, and that you would be a fool to think otherwise.

But is he some kind of entrepreneurial genius? Let’s turn to Dave Karpf for a different perspective. Karpf, in his Substack post, Elon Musk and the Infinite Rebuy, examines Musk’s approach to being successful by way of example:

There’s a scene in Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Elon Musk that unintentionally captures the essence of the book: [Max] Levchin was at a friend’s bachelor pad hanging out with Musk. Some people were playing a high-stakes game of Texas Hold ‘Em. Although Musk was not a card player, he pulled up to the table. “There were all these nerds and sharpsters who were good at memorizing cards and calculating odds,” Levchin says. “Elon just proceeded to go all in on every hand and lose. Then he would buy more chips and double down. Eventually, after losing many hands, he went all in and won. Then he said “Right, fine, I’m done.” It would be a theme in his life: avoid taking chips off the table; keep risking them. That would turn out to be a good strategy. (page 86) There are a couple ways you can read this scene. One is that Musk is an aggressive risk-taker who defies convention, blazes his own path, and routinely proves his doubters wrong. The other is that Elon Musk sucks at poker. But he has access to so much capital that he can keep rebuying until he scores a win.

So Musk wins at poker not by being the most competent poker player: he wins by overwhelming the other players with his boundless resources. And it’s not just poker where he uses this approach to succeed. Karpf adds:

Musk flipped his first company (Zip2) for a profit back in the early internet boom years, when it was easy to flip your company for a profit. He was ousted as CEO of his second company (PayPal). It succeeded in spite of him. He was still the largest shareholder when it was sold to eBay, which netted him $175 million for a company whose key move was removing him from leadership. He invested the PayPal windfall into SpaceX, and burned through all of SpaceX’s capital without successfully launching a single rocket. The first three rockets all blew up, at least partially because Musk-the-manager insisted on cutting the wrong corners. He only had the budget to try three times. In 2008 SpaceX was spiraling toward bankruptcy. The company was rescued by Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund (which was populated by basically the whole rest of the “PayPal mafia”). These were the same people who had firsthand knowledge of Musk-the-impetuous-and-destructive-CEO. There’s a fascinating scene in the book, where Thiel asks Musk if he can speak with the company’s chief rocket engineer. Elon replies “you’re speaking to him right now.” That’s, uh, not reassuring to Thiel and his crew. They had worked with Musk. They know he isn’t an ACTUAL rocket scientist. They also know he’s a control freak with at-times-awful instincts. SpaceX employs plenty of rocket scientists with Ph.D.’s. But Elon is always gonna Elon. The “real world Tony Stark” vibe is an illusion, but one that he desperately seeks to maintain, even when his company is on the line and his audience knows better. Founders Fund invests $20 million anyway, effectively saving the company. The investment wasn’t because they believed human civilization has to become multiplanetary, or even because they were confident the fourth rocket launch would go better than the first three. It was because they felt guilty about firing Elon back in the PayPal days, and they figured there would be a lot of money in it if the longshot bet paid off. They spotted Elon another buy-in. He went all-in again. And this time the rocket launch was a success. If you want to be hailed as a genius innovator, you don’t actually need next-level brilliance. You just need access to enough money to keep rebuying until you succeed.

It seems that the path to success for Musk is not to be good at something, but to be tenacious and throw massive amounts of resources at a problem until you defeat it.

In IT, there is an approach to solving problems like this called the Mongolian horde approach. In the Mongolian horde approach, you solve a problem by throwing all the resources you can at it. It’s not the smartest or most cost effective approach to problem solving, but if a problem is difficult and important, it can be an effective way to deal with it.

It’s interesting that Smith touches on this approach in his post. He brings up Genghis Khan, the leader of the Mongols:

Note the key example of Genghis (Chinggis) Khan. It wasn’t just his decisions that influenced the course of history, of course; lots of other steppe warlords tried to conquer the world and simply failed. Genghis might have benefited from being in just the right place at just the right time, but he probably had organizational and motivational talents that made him uniquely capable of conquering more territory than any other person in history. The comparison, of course, is not lost on Elon himself

It appears that Musk is familiar with the Mongolian Horde approach as well. Indeed, Karpf illustrates the number of times Musk used this approach in order to be successful, whether it’s playing poker or building rockets.

If you can take this approach, with persistence and some luck, you can be successful. Success might come at a great cost, but it likely will come. And in America, if you are successful, people assume you are intelligent and highly competent regardless of your approach. That’s what Smith seems to assume in his post on Musk.

Even with this approach, you do have to have some degree of competency. If you are using this approach to play poker, you have to know enough about the game to win when the opportunity presents itself. But you don’t have to be the world’s best poker player or even a good poker player.

The same holds true for Musk and his other companies. He’s not incompetent, but he’s not necessarily great or even good at what he does. He just hangs in there and keeps applying overwhelming resources until he eventually wins. His access to resources and his tenacity are impressive: his competency, not so much.

P.S. Like many others, I used to think Musk was highly competent. I stopped thinking that when he took over Twitter and turned it into X. This “Batshit Crazy Story Of The Day Elon Musk Decided To Personally Rip Servers Out Of A Sacramento Data Center” in Techdirt convinced me his IT competency is not much better than his poker competency. Indeed, if success was a metric, then he is incompetent at running tech companies, based on this piece in the Verge: Elon Musk email to X staff: ‘we’re barely breaking even’. I won’t count him out until he abandons X, but if the time comes when X is successful, it will be because of him applying massive amount of resources (time, money, etc) to it, not because he is an IT genius.

I often talk about exercise from a physical point of view, but not from a mental point of view. I thought I should expand my idea of exercise when I came across this quote from G.K. Chesterton:

I often talk about exercise from a physical point of view, but not from a mental point of view. I thought I should expand my idea of exercise when I came across this quote from G.K. Chesterton:

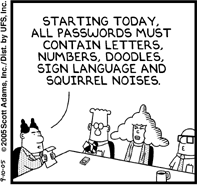

There were two Scott Adams: the one known for being the creator of Dilbert, and the one who recently passed away who was beloved by right wingers in America. People like me who knew the first Scott Adams and who loved his Dilbert comic in the 90s were dismayed when he morphed into the second Scott Adams.

There were two Scott Adams: the one known for being the creator of Dilbert, and the one who recently passed away who was beloved by right wingers in America. People like me who knew the first Scott Adams and who loved his Dilbert comic in the 90s were dismayed when he morphed into the second Scott Adams.

It’s difficult to not think about migrants and natives. So many problems in the world have their roots in who belongs to a place and when. So I was interested to hear about this book: Home Rule – National Sovereignty and the Separation of Natives and Migrants from Duke University Press. The Duke University Press says:

It’s difficult to not think about migrants and natives. So many problems in the world have their roots in who belongs to a place and when. So I was interested to hear about this book: Home Rule – National Sovereignty and the Separation of Natives and Migrants from Duke University Press. The Duke University Press says: If you want to read some thoughtful posts today, I highly recommend

If you want to read some thoughtful posts today, I highly recommend

You may only think of transportation in a practical sense of how you travel from A to B. However, there are many hidden assumptions in your travels, including ideas about Comfort, Cost and Convenience. And those three C words got me thinking about another C word, Class.

You may only think of transportation in a practical sense of how you travel from A to B. However, there are many hidden assumptions in your travels, including ideas about Comfort, Cost and Convenience. And those three C words got me thinking about another C word, Class.

A good mediation on fire can be found here:

A good mediation on fire can be found here:

It’s ok to hate August and love February (and vice versa. Or neither.)

It’s ok to hate August and love February (and vice versa. Or neither.)

Waste is a failure of imagination. Woodworkers know that especially. Good wood workers will try and

Waste is a failure of imagination. Woodworkers know that especially. Good wood workers will try and